Hope Amidst the "Ruined"

Huntington Theatre Company presents a gripping production of Lynn Nottage’s "Ruined," the Pulitzer Prize-winning play that takes an unflinching look at the savagery of war and sees survival

“Ruined,” Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play about the ability of Congolese women to survive unimaginable brutality at the hands of countrymen at war, is both repulsive and riveting – and not to be missed.  Nottage, director Liesl Tommy, and the entire Huntington Theatre cast have managed to do the impossible. They have embraced the indestructible humanity that enables the world to maintain hope while exposing the unspeakable savagery that continues to run rampant throughout East Africa – despite an “official” end to that region’s catastrophic civil war in 2002.

Nottage, director Liesl Tommy, and the entire Huntington Theatre cast have managed to do the impossible. They have embraced the indestructible humanity that enables the world to maintain hope while exposing the unspeakable savagery that continues to run rampant throughout East Africa – despite an “official” end to that region’s catastrophic civil war in 2002.

Through the voices of the play’s victimized women, “Ruined” speaks for all women who somehow manage to hold onto their courage, faith, and ability to dream even in the face of rape, torture, kidnapping and abandonment. They also speak for the Congo itself, whose land and resources are equally destroyed by foreign exploiters and warring tribes. Alternately punishing and poetic, Nottage’s script shocks the breath out of the audience one minute and elicits tears of hope the next.

At the center of “Ruined” is Mama Nadi (Tonye Patano), a street-smart, no-nonsense, wise-cracking matron whose ramshackle barroom/brothel serves as a fragile oasis amidst the Congo’s overwhelming chaos. Mama maintains a meager civility in her tiny corner of the world by taking no side but her own, serving customers of all persuasions as long as they park their guns – and their politics – at the door. Befriending all, she courts respect from government militia, rebel freedom fighters, indentured coltan miners, and outside opportunists who gain substantial wealth by fencing valuable conflict minerals to the world’s biggest technology firms.

Mama also provides a safe haven of sorts to young refugee women whom she presses into service as prostitutes in exchange for food, shelter, and a very small percentage of the take. Her approach is a simple one.  Either sell yourself in a controlled environment or be raped and tortured on your own. While Mama’s pragmatism at first appears cold and self-serving, it ultimately proves to be an essential survival mechanism – for herself and all the women in her tenuous care.

Either sell yourself in a controlled environment or be raped and tortured on your own. While Mama’s pragmatism at first appears cold and self-serving, it ultimately proves to be an essential survival mechanism – for herself and all the women in her tenuous care.

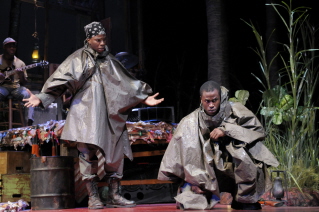

The delicate balance that Mama maintains in her modest retreat is disrupted, however, when Christian (Oberon K.A. Adjepong), her affable traveling salesman/supplier, prevails upon her to take in two new young women, Sophie (Carla Duren) and Salima (Pascale Armand). Both victims of devastating horror at the hands of marauding soldiers and subsequent rejection by their families for being thusly “ruined,” the unassuming girls unwittingly draw the war inside Mama Nadi’s by taking determined stands against further indignities.

Duren, Armand, and Zainab Jah as Josephine, once a tribal princess now also harbored at Mama Nadi’s, give magnificent performances, painting unflinching portraits of abduction and mutilation in one breath and sharing girlishly innocent romantic fantasies in the next. They each reveal a core of indefatigable dignity beneath their horrific scars and unrelenting fears. They also, remarkably, find moments of joy and humor. Patano as Mama is a tower of self-made strength, determined and confident in the emotional armor she has built for herself but ever aware that her house of cards could come toppling down in one violent wind. She allows herself no illusions of a better life. To dream would be to become vulnerable to feelings. Whenever Christian’s flirtations threaten to soften her resistance, she deflects his attentions with affectionate derision.

As Christian Adjepong is Everyman of the Congo, the morally upright individual trying to survive the fray by remaining neutral on the fringes. His balance is disrupted, too, however, when the frightening  Commander Osembenga (Adrain Roberts) of the government militia forces him off the wagon and into a downward spiral – not into a brainless stupor but rather ironically into a rebellious clarity that sharpens instead of numbs his pain. Adjepong makes Christian’s torment as gut-wrenching as he makes his exuberant charms delightful. He is the kind of thoughtful and considerate man upon whom the Congo’s hopeful future will depend.

Commander Osembenga (Adrain Roberts) of the government militia forces him off the wagon and into a downward spiral – not into a brainless stupor but rather ironically into a rebellious clarity that sharpens instead of numbs his pain. Adjepong makes Christian’s torment as gut-wrenching as he makes his exuberant charms delightful. He is the kind of thoughtful and considerate man upon whom the Congo’s hopeful future will depend.

Underscoring the tragedy and triumph in “Ruined” is haunting music performed by a guitarist and a percussionist (Alvin Terry and Adesoji Odukogbe) who remain seated on an elevated nightclub stage throughout the play. Their playing can be tender and sweet when the angelic young Sophie sings of the sun and the stars, or they can suddenly turn jubilant African rhythms into dark pulsating beats when soldiers turn sexually charged dance numbers into ugly ominous attacks. And it doesn’t matter which soldiers are in Mama Nadi’s at any given time. Government militia or rebel insurgents, they’re two sides of the same coin. Their uniforms may be different, but their inhumane actions are the same. It’s no coincidence that the same actors double as opposing forces.

Ultimately “Ruined” graphically depicts the incomprehensibly destructive power of war and greed that turns a majestic country into a wasteland and innocent women and children into spoils of war. But miraculously, it also conveys the unrelenting power of hope that drives the human spirit to survive. Even when an oasis crumbles, humanity and dreams stay alive.

PHOTOS BY KEVIN BERNE: Zainab Jah as Josephine, Carla Duren as Sophie, and Pascale Armand as Salima Salima; Oberon K.A. Adjepong as Christian and Tonye Patano as Mama Nadi; Okieriete Onaodowan as Simon and Jason Bowen as Fortune

and four dramatic injuries to major cast members within four weeks – may turn out to be the best thing to hit the Great White Way in decades. Oh, artistically this brainchild of U2’s Bono, the Edge, and director Julie Taymor may crash and burn once bono fide theater critics are finally invited to see what all the hoopla is about. For now, however,

and four dramatic injuries to major cast members within four weeks – may turn out to be the best thing to hit the Great White Way in decades. Oh, artistically this brainchild of U2’s Bono, the Edge, and director Julie Taymor may crash and burn once bono fide theater critics are finally invited to see what all the hoopla is about. For now, however,  Foxwoods Theatre – needed to accommodate the never-before-seen flying sequences planned by Taymor – were completed, and new (lesser known) Broadway actors were cast in the roles vacated by the high-profile stars. A new opening was set for the fall of 2010 and it looked like Spider-Man would actually take flight.

Foxwoods Theatre – needed to accommodate the never-before-seen flying sequences planned by Taymor – were completed, and new (lesser known) Broadway actors were cast in the roles vacated by the high-profile stars. A new opening was set for the fall of 2010 and it looked like Spider-Man would actually take flight. The most chilling blow to the show, however, came on December 20 when lead Spider-Man stunt double

The most chilling blow to the show, however, came on December 20 when lead Spider-Man stunt double  Once he is cleared from rehab, he wants to get back in his harness and again careen from rafter to rafter at upwards of 50 mph.

Once he is cleared from rehab, he wants to get back in his harness and again careen from rafter to rafter at upwards of 50 mph. Given the immensely complicated sets, costumes, flying sequences, and special effects, the show is reportedly an unruly behemoth that would require months of reworking – and millions of additional dollars – to make good on its lofty promise. At this late date, can changes that would make the story more coherent and the music more engaging realistically be incorporated? Given the massively technical nature of the show, probably not. Of course, despite its problems, the spectacle that is Spider-Man may continue to attract sell-out audiences. Only time will tell if the sporadic thrills induced by the thought of an accident waiting to happen are enough to keep people satisfied. But wouldn’t it be grand if the Spider-Man saga ended up encouraging Broadway movers and shakers to return their creative focus first and foremost to telling really good stories? Production values should visually interpret and enhance the material, not overwhelm it. Perhaps the lesson to be learned here is that less really can be more.

Given the immensely complicated sets, costumes, flying sequences, and special effects, the show is reportedly an unruly behemoth that would require months of reworking – and millions of additional dollars – to make good on its lofty promise. At this late date, can changes that would make the story more coherent and the music more engaging realistically be incorporated? Given the massively technical nature of the show, probably not. Of course, despite its problems, the spectacle that is Spider-Man may continue to attract sell-out audiences. Only time will tell if the sporadic thrills induced by the thought of an accident waiting to happen are enough to keep people satisfied. But wouldn’t it be grand if the Spider-Man saga ended up encouraging Broadway movers and shakers to return their creative focus first and foremost to telling really good stories? Production values should visually interpret and enhance the material, not overwhelm it. Perhaps the lesson to be learned here is that less really can be more.